Could the global outreach of Covid-19 lead to the next major shock to the Global System? This was the question I asked myself in January while observing the developments as regards the Covid-19 outbreak in Wuhan, China. Later on, I published an article claiming that the disruption of the global supply chains due to the outbreak of Covid-19 is to be seen as the canary in the Global System mine.

Furthermore, I stressed that the markets had not anticipated the long-term disruptions of global supply chains, nor had they priced the real stress on the globalized networks as well as on the global flows of goods, people and services prior to the global outreach of the Covid-19. I concluded in mid-February that the Covid-19 pandemic would further aggravate the ongoing economic slowdown and trade stagnation and might even result in a yet unprecedented major shock to the Global System.

What happened next?

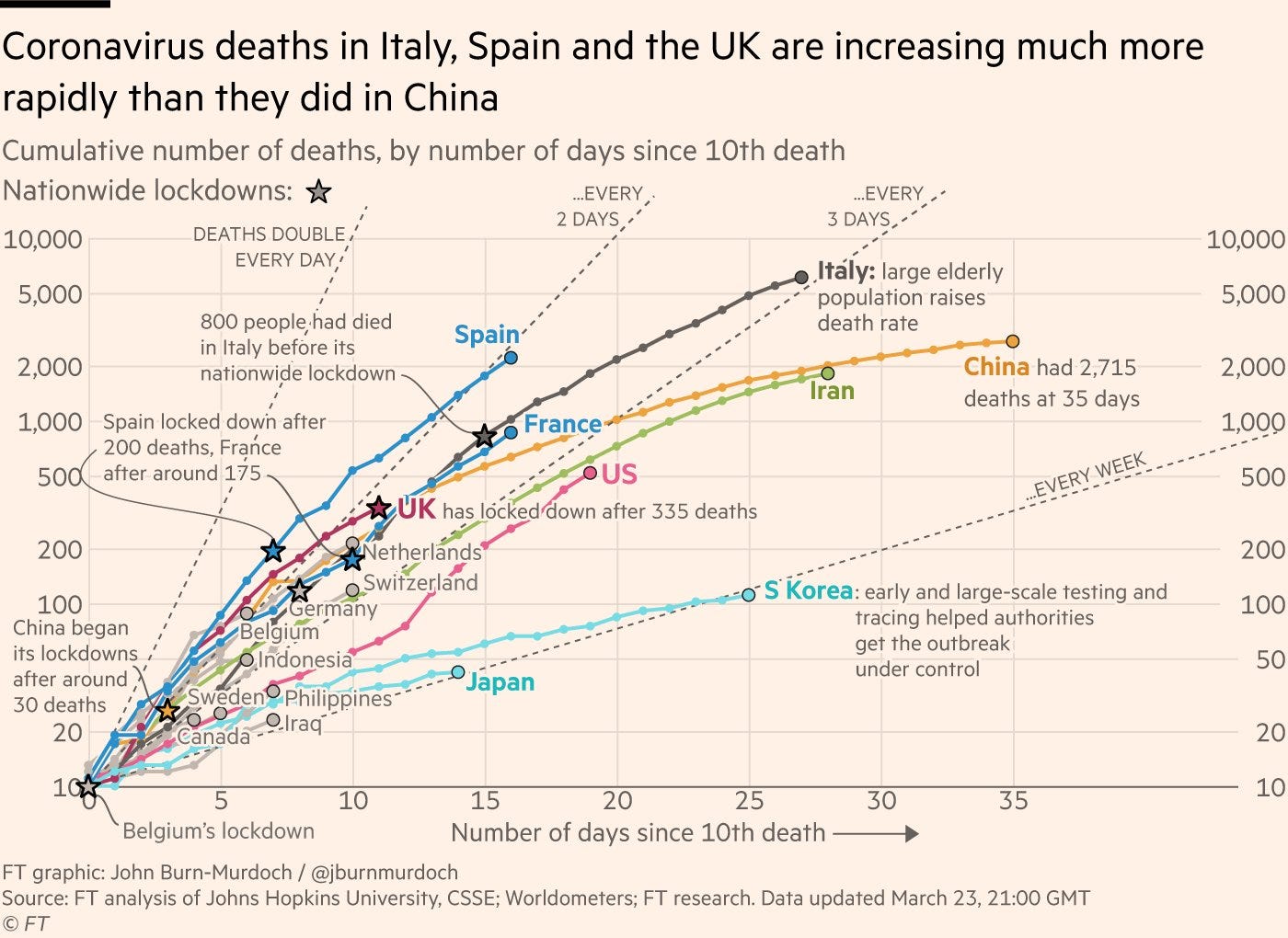

First, the Coronavirus has spread much quicker to other parts of the world than any government had anticipated or prepared for. Meanwhile, most of the seriously affected countries have introduced very restrictive measures to slow down any further Covid-19 spread. These measures and actions are well documented and data is available on the Internet. I will particularly focus on the concrete effects on the Global System as outlined in my article from February.

First, it is important to emphasize that the Global System was already put under pressure due to the systemic decoupling between the USA and China as well as cyclical processes such as an ongoing global economic slowdown, trade stagnation, and liquidity crisis prior to Covid-19 crisis. Systemic risks show multiplicative dynamics that are often ignored or misunderstood due to their higher-order effects. Against this background, the Covid-19 became an accelerator of the sum of various minor shocks to the system and thus the global virus outreach exemplified another systemic risk emerging from the interconnectedness of the Global System.

The Systemic Risk Council summarized the current state of the Global System in its recently published statement as follows:

“Unlike 2007/08, this is not a financial implosion that threatens the economy and society. It is not a shock from within the economy that threatens the stability of the financial system. It is a devastating shock to people’s health that threatens their livelihoods, the businesses in which they work and invest savings, the wider economy, and therefore the financial system. Weaknesses in the financial system are exacerbating the potential feedback loops, which risk deepening the downturn and impeding eventual economic recovery.”

Taking the example of Covid-19, the pandemic not only put the health systems under unforeseen stress but led to an unprecedented partial economic and trade shutdown in developed and developing economies. Meanwhile, the JPMorgan estimations of the Covid-19 impact on the US economy pointed to a drop by 2% in the first quarter and 3% in the second, while the Eurozone GDP could contract by 1.8% and 3.3%. Furthermore, JPMorgan concluded:

“As we resign ourselves to the inevitability of a large and broad-based shock to global growth, the key issue is whether we can avoid a traditional and longer-lasting recession event.”

Other key financial institutions presented even grimmer prognoses for the second quarter of 2020 and pointed to global recession trends. Deutsche Bank assessed the situation as follows:

“substantially exceed anything previously recorded going back to at least World War II.”

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis President James Bullard even outlined an unprecedented 50% decline in the US GDP. It is obviously no longer about the confirmation of the global recession prognoses that were made prior to the Covid-19 crisis. We are potentially sliding into a global depression in a much more interconnected Global System than during the Great Financial Crisis 2007/08, let alone the Great Depression in 1929. In fact, Nouriel Rubini referred to these forecasts as “depression growth rates”.

“In the face of the most serious global health crisis in more than a century, fiscal and monetary policy makers around the world will have to pull out all the stops to prevent what currently looks like an inevitable recession from turning into a depression,” according to Joachim Fels of Pacific Investment Management Co.

“Extraordinary times require extraordinary action”

The global financial and economic system witnessed coordinated monetary stimulus and bold fiscal responses by the Central Banks and the Governments of the developed economies on both sides of the Atlantic that were not seen before. The European response came from both layers — the institutional (ECB) and the national (the member states). The European Central Bank (ECB) launched a Pandemic Emergency Purchase €750bn ($820bn) package to mitigate the Covid-19 shock. The president of the ECB even stressed that there were no limits to the ECB commitment to the Euro. The European Commission announced further €37bn under its regional funding programmes to combat the impact of the pandemic. The major European economies disclosed massive financial packages too (Germany — €500 billion, the UK — £350 billion, France — €345 billion, just to name a few).

At the same time, the Federal Reserve cut interest rates to almost zero and launched a $700bn stimulus program. Furthermore, the Federal Reserve announced the establishment of temporary U.S. dollar liquidity arrangements (swap lines) with other central banks — the Reserve Bank of Australia, the Banco Central do Brasil, the Danmarks Nationalbank (Denmark), the Bank of Korea, the Banco de Mexico, the Norges Bank (Norway), the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, the Monetary Authority of Singapore, and the Sveriges Riksbank (Sweden). Finally, the Federal Reserve even pledged asset purchases with no limit to support the markets as part of a massive new package. This was described as “QE infinity” territory and it remains to be seen whether other Central Banks will follow suit with their QE programs.

One conclusion that may be drawn from this first stage of unprecedented measures and actions is that it is not about the Too Big To Fail (TBTF) banks this time but the Too Many To Fail small businesses, entrepreneurs, working-class and middle-class people, who will be the target of the bailout programmes first and foremost.

We are just at the beginning of the greatest uncertainty in the last hundred years cycle, particularly as regards the future of the Global System coupled with potential major shocks to its main socio-economic systems due to the unforeseen disruptions and cascading effects within the interconnected networks, occurring with much higher speed and greater scale than any government or institution could respond to.

To conclude with the final statement by The Systemic Risk Council:

“If things deteriorate a lot more, whether quickly or slowly, governments may find themselves facing the question, not seen outside major wars, of whether to steer the economy’s production priorities, whether to support household spending with subsidies and welfare payments much higher than in normal circumstances, and whether to fund themselves via their jurisdiction’s monetary authority. Obviously the threshold for steps of that kind should be very high given the interference with normal freedoms and constraints. But governments should be conducting contingency planning to think through the issues in advance rather than, however remote it seems, being overtaken by events.” (SRC, 19. March 2020).

What could be a tipping point for the Global System against this background of major shocks and transformational processes?

My main long-term Global System scenarios remain as follows: 1) either a “violent” systemic decoupling encompassing all socio-economic systems (currency, trade, financial, diplomatic, etc. networks) or a systemic co-existence between US-led and China-led blocs in the long run. But this will be the topic of another input.

Velina Tchakarova

Velina Tchakarova

Velina is Head of Institute at the Austrian Institute for European and Security Policy (AIES) in Vienna.

Originally published in: Medium

Velina Tchakarova

Velina Tchakarova